How Pokémon's arrival in the UK changed Games Workshop forever

"It was a wake-up call to remind us what we really did for a living."

A few years ago, I was changing costumes between scenes in a period drama, stepping out of 18th Century workwear and into some noble's finery, when a fellow cast member told me something I had never expected to hear. They had worked at Games Workshop for many years, and they told me that when Pokémon arrived in the UK, it nearly brought the company - Games Workshop - to its knees.

My reaction was probably as yours is now: I missed the hole of my stockings and almost fell over. I couldn't quite believe what I was hearing. Pokémon, that very cheery cartoon of an IP, had nearly levelled the grim-dark house of Warhammer? Was I dreaming?

It's a thought I had to swallow as the play raced on, and though I followed it up with my friend afterwards, nothing more came of it. Time moved on and the story faded away. But I never forgot it. So when it surfaced in my mind earlier this year, I decided to do something about it.

I began by digging around in Games Workshop's financial records on the government's website. I sifted through a decade's worth of documents, figuring that surely if something like this had happened, there would be a record of it.

If you didn't know, Pokémon arrived in the UK in 1999, having originated three years earlier in Japan. Maybe you remember. I was 17 years old when it arrived so I skewed slightly older than the intended audience, but I do remember being impressed by the GameBoy games and I couldn't help but notice the cartoon on TV. The trading card game, though, passed me by. Anyway, this meant the financial report I was looking for was for the year 2000, enough time to give Pokémon a chance to land.

Success, I found it, and almost immediately something in it caught my eye: suspicious remarks made by chairman Tom Kirby in reference to UK sales. "By our own standards this has been a disappointing year," he wrote. Then he added, cryptically: "There has been some loose talk recently questioning the health of the Games Workshop Hobby." (The Hobby is how GW execs refer to the miniatures business.) "The Hobby is in rude health, and is continuing to spread profitability around the world."

Loose talk? Why would Kirby feel the need to say something like that unless Games Workshop was under threat?

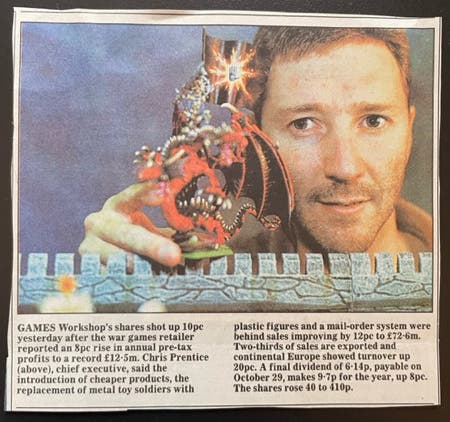

I read on - and made my biggest discovery yet. It was a remark made by Chris Prentice, Games Workshop CEO at the time, in reference to those disappointing UK sales. "For some time now we believe that an element of our UK like-for-like growth has been achieved by increasing the appeal of our stores at the lower end of the customer age range," he wrote. "We do not believe that many of these youngsters are capable of truly participating in all aspects of a complex hobby, which involves reading, painting and strategic thinking.

"Consequently," he added, and this is the important bit: "we have allowed our customer base to become vulnerable to toy fads. Last year we saw a sharp decline in sales to this age group."

Toy fads! That must be it. What else could he mean but Pokémon? It was my best indication yet that something had happened at Games Workshop because of it. All I needed now was someone to say "Pokémon" on the record. But I read and read and I couldn't find any explicit mention of it. And I read the following year's reports and there was nothing there either, nor for the year after, nor in any of the company's financial reports. Chris Prentice's "toy fads" was the best I had.

What's more, the reports didn't show any significant drops in income and profit, or even suggestive dips. All the graphs I saw went up and up and up, and all the year-on-year sales I read about seemed to increase. None of this suggested to me a company on its knees.

Determined not to give up, though, I took to Twitter to see if I could find anyone who had worked at Games Workshop at the time, to see whether they remembered anything about Pokémon's arrival and impact. And to my surprise, some people did.

One person, who worked in a Worcester Games Workshop store, told me there was a newsagent down the street where kids would buy Pokémon cards before walking into their store to open them. This was not on. "We had to set a precedent quite early on that as well as the obvious expectations of not playing Pokémon in our GW store, or that the kids were not to loiter directly outside the front playing it too," they said.

Another person, who worked in a Bedford Games Workshop store, told me a lot of people would come in asking to buy Pokémon cards, which the shop obviously didn't sell, so they'd have to send them around the corner to GAME instead. I even heard from one person that Games Workshop would use Pokémon in training meetings as an example of why their hobby was superior, though this was as detailed as the story got.

But whether or not people personally noticed 'a Pokémon effect' (and some did, but equally, some did not) they all unanimously agreed on one thing: that Games Workshop wasn't impacted in any meaningful way by Pokémon. It's not what I wanted to hear.

What I wanted to hear - what I really wanted to hear - was why Chris Prentice had called out a "toy fad" way back in that 2000 financial report. What had pushed him to make that comment? Was it Pokémon?

But Prentice left Games Workshop almost as long ago as he made those remarks, and he doesn't work in the industry any more. He doesn't have much of a LinkedIn presence, nor does he have much of an online presence. He's not someone, clearly, who puts themselves forward and welcomes being found.

"You did well to track me down," Chris Prentice tells me with a smile when we finally meet on a video call. He's sitting in an airy office in what appears to be a nice home, and he appears to be as well kept as I imagine a former CEO to be. Neat and trim, everything in order. But while it's a victory tracking him down, I still need to know whether Pokémon had any notable effect on Games Workshop. And I wonder whether he'll remember any of it at all.

But another victory. "I remember it very well," he says. Would you believe that I caught him mid-memoir writing when I asked to talk to him? It's a hell of a coincidence. "And that," he tells me, referring to the Pokémon situation, "was absolutely one of the stories that I wrote up."

So it was Pokémon! And, apparently, it was a big enough deal that he not only remembers it all these many years later, but thinks it worthwhile writing up. Then comes another surprise: Prentice tells me about a crucial piece of information I missed, which would have made everything abundantly clear.

"In probably May-June 2000 we made a profit warning," he says, "and we included the game known as 'the p-word' in that profit warning, saying that basically Pokémon had hit our UK business - and our UK retail business in particular - quite hard and that was going to cause a gap in our profitability for the year."

That's exactly the kind of thing I'd been looking for - specific mention of Pokémon in a company document. So why hadn't I found it? I combed back over the online records to check, but I still couldn't see it there. Because it wasn't and isn't. For some reason, that one document has disappeared. [Update: It hasn't disappeared. Filings like this live in a different place. Thanks, commenter mini-mana-munu!]

But back to Prentice: "Just to give you a sense of the scale: by March/April time, we were suffering a thirty percent decline in our UK retail stores - a really significant downturn."

It was significant enough for the company not to meet its profit expectations, which in turn meant issuing the profit warning, something no one ever wants to do. And all because of Pokémon. Or was it?

"This is my take on why it had an impact," Prentice says.

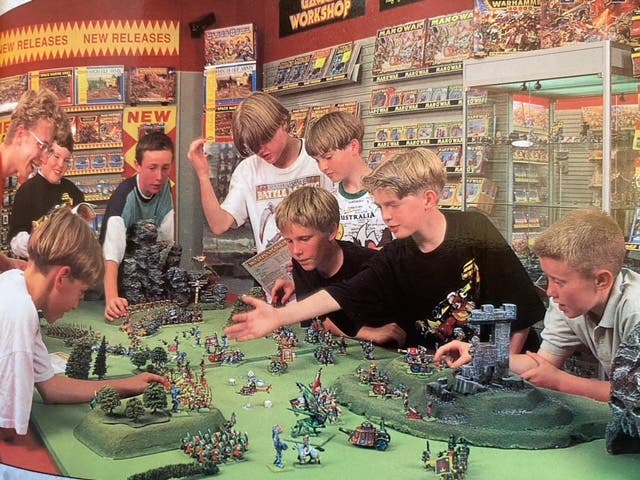

"My view was our UK retail chain, which at the time was probably approaching a hundred stores, had been aggressively chasing like-for-like growth, and the way in which they'd been doing that was to dumb down what we saw as a more sophisticated hobby - involving modelling, painting, gaming - probably for teenage boys and teenagers upwards. And in order to keep that like-for-like growth going, our UK management at the time, I feel, had been dumbing it down a little bit and bringing in a lot of younger customers.

"Now that looked great in the numbers because they were spending money," he adds, "but I don't think they were ever truly engaged with the depths of the hobby that we'd created. So when Pokémon came along [in] early 2000, it was a shiny new thing for the nine, ten, eleven year-olds, maybe even the twelve year-olds - the ones that were pre-teen and therefore weren't necessarily fully engaged with our hobby. And they just stopped coming to our stores."

Prentice believes it was a problem of Games Workshop's own making. By bending out of shape to target a younger audience, the company had made itself vulnerable to any "toy fads" that might arrive and sway the audience from it. Theoretically, it could have been anything. "It wasn't Pokémon at all," Prentice says, "it was the younger customer base and that group putting off our core gamers - our older customer base."

However, while this all sounds very dramatic, it's important to have some context, because while Pokémon certainly had a significant impact on a part of the Games Workshop business, it didn't do anything like - to labour the metaphor a bit - bring Games Workshop to its knees.

Pokémon was a very isolated problem. "We didn't see a 'Pokémon effect' anywhere other than our UK retail chain," Prentice tells me. And that UK retail chain was only one part of the UK business, and that UK business was only one part of a global company. That's why I didn't see anything obvious on the graphs, because overall, Games Workshop was fine. "It wasn't anything like life-threatening," Prentice says.

It was, however, uncomfortable. And even though Pokémon didn't fell Games Workshop, it did have a significant and lasting effect upon the company's operations as a whole. "It was a wake-up call to remind us what we really did for a living," Prentice says. "And what we had to do was reinvigorate ourselves and make the stores a more attractive place for more experienced gamers."

Still, though, Prentice faced division from within. There remained those among the Games Workshop higher-ups who believed a younger audience really was the way to go. "We certainly had one strong faction that would have argued that reducing the age profile was an entirely good thing," Prentice says, "capturing them earlier, keeping them longer, producing Junior Warhammer, let's call it - an easy clip-together version with different colour armies playable right from the box. Rather than the more complicated building models, painting... The more sophisticated hobby. And that was a tension that was in the business certainly the whole time I was there."

But Prentice's side got the upper hand and the company implemented a cross-business working party to refocus Games Workshop on who they believed the core customers really were: the older audience. And it worked. Within six months the company was apparently back in double-digit growth. "We recognised the problem, got together, came up with a plan to put it right and put it right," Prentice says.

Were it not for Pokémon, who knows where Games Workshop would be today? Pikachu and pals left a dent on the Warhammer company in a way few other competitors - likely or unlikely - apparently have. "I'm not entirely sure I can remember anything else impacting in the same way at all," Prentice says. The exception being The Lord of the Rings licence which, bolstered by the enormous popularity of the Peter Jackson films, skyrocketed Games Workshop's sales.

Pokémon's impact also had lasting ramifications for Prentice's career personally at Games Workshop, contributing to his resignation in December 2000, a few months after his "toy fads" remark. "Three profit warnings in two years is not a good track record for a chief exec, is it?" he tells me and smiles. "I know we were doing the right things and I'm absolutely certain I left the business in a much stronger place than I found it, but yeah, [Pokémon] will have been a contributing factor [in my resignation] but not one I hold against it!"

In the years since Games Workshop, Chris Prentice has owned a business designing and distributing outdoor accessories, called Trekmates, and was on the board at homeless charity Framework. These days, he's chair of the board at innovative design company Zak Mobility, which I kid you not, has literally redesigned the wheel, and he tells me he's involved in some other projects due to launch next year. He remembers his time at Games Workshop fondly. It's not clear if he's a fan of Pokémon.