Mediterranea Inferno review - a bruising, intensely stylish post-COVID nightmare

Mirage à trois.

So how was your lockdown? Three years on, as the 'new normal' rapidly recedes, life under COVID restrictions feels almost like a fever dream, any thought to the lingering trauma of enforced isolation ignored, dismissed, or forgotten. Mediterranea Inferno, though, remembers. This second outing from The Milky Way Prince's Lorenzo Redaelli – a creator working in the shadow of Italy's stringent, long-lasting coronavirus measures – has a lot on its mind, beginning with the impact those wilderness years have had on the collective conscious, particularly on young adults grappling with a sense of lost time at a critical juncture in their lives.

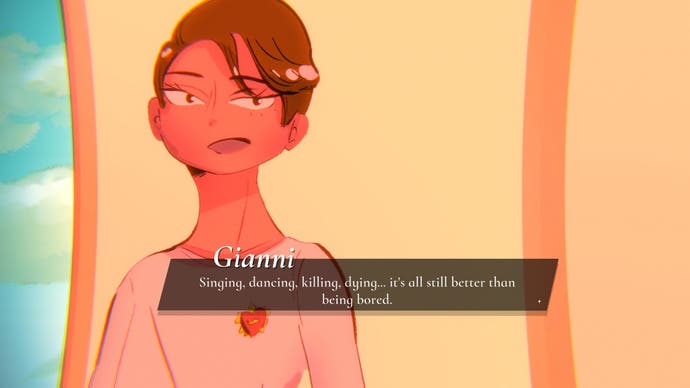

More than that, it presents – albeit in an exaggerated, darkly humorous fashion – a vision of paralysing generational malaise in the face of an uncertain present, a diminishing future, and eroding protections for vulnerable minorities. It's anxiety piled upon trauma, distilled into Mediterranea Inferno's three leads: a trio of beautiful, fashionable, popular Milan club kids in their early 20s – collectively known as 'I ragazzi del sole', the Sun Guys – who between them represent something of a holy triumvirate of identity, sociality, and power.

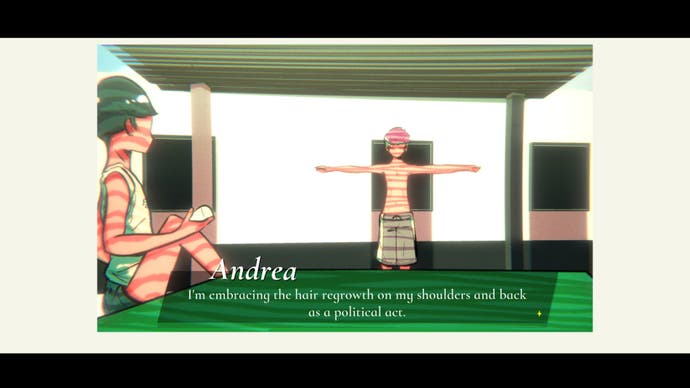

With our trio introduced, time smash-cuts to August 2022 when, after two years apart due to Italy's lingering COVID restrictions, the previously inseparable friends reunite in the blazing heat of a southern Italian summer. Each, though, has been changed by the trauma of the intervening years; Claudio, the once charismatic, confident leader of the group, is struggling to find his identity in a cultural and generational void; Andrea, previously the life of the party, feels hollowed in the absence of any real human connection, and only Mida, once aloof and uncertain, seems to have moved forward, having landed an influential, jet-setting modelling gig during lockdown. And while the boys soon settle into their old rhythms, there's a simmering undercurrent of tension, dysfunction, and perhaps even resentment, as long-held and newfound insecurities fester, and their three-day vacation in Puglia threatens to implode.

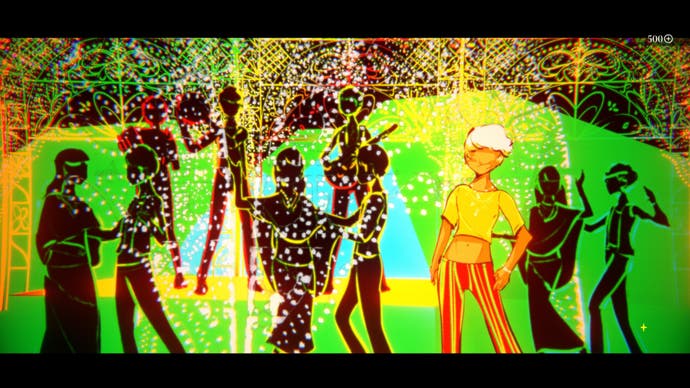

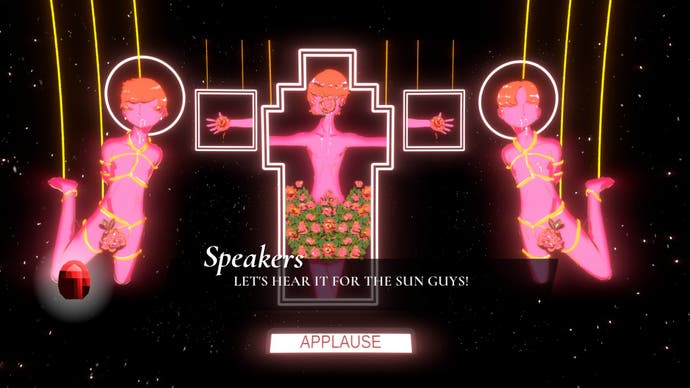

Mediterranea Inferno is, foundationally, a visual novel, but Redaelli's idiosyncratic vision, masterful control of the form, and dazzling artistic sensibilities create an experience that feels unbounded. Much of its story is conveyed through text, yes, but here the written word is in a perpetual dance with Redaelli's seductive score, sparing soundscapes, and breathlessly inventive visuals – shifting, surprising fusions of 2D artwork and stylised 3D, channelling the likes of fashion photography, classic Italian cinema, and Catholic imagery – which form a precise presentational language so ferociously intense, the cumulative effect is all-consuming.

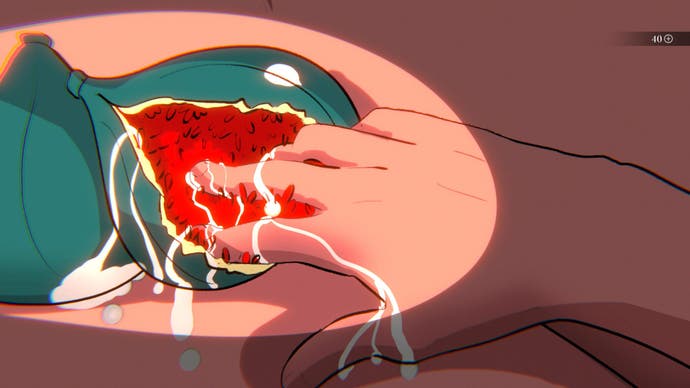

Here, the Italian summer is, initially at least, rendered like hell itself, an engulfing, stifling swell of vicious red that blasts and bleeds through every frame; wild prickly pears throb suggestively, menacingly, as if something is ready to burst from within, while drab evenings in the boys' villa are painted like a comedown after each vivid day. Amid all this comes a stranger bearing the Fruit of Mirages, each bite promising a temporary escape from the pain of the last few years – perhaps even a truly "endless summer" of pleasures for those ready to fully indulge. "I know you're looking for Mirages," the enigmatic Madama tells the boys. "I sell desires, hopes. I have the key to solve all your problems. I can cure your pain. I can give you what the world cannot".

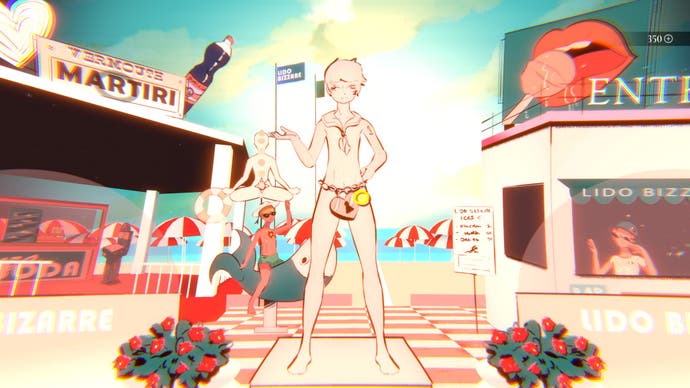

For the low, low price of 350 "summer coins", earned at fixed points throughout each day, one boy – as selected by the player – can experience his own Mirage, whereupon Mediterranea Inferno's already heightened reality begins to untether completely, the postcard-perfect Italian summer twisting in a reflection of each lead's fragile psyche. During these hallucinatory sequences, Mediterranea Inferno loosens its narrative grip a little, providing an opportunity to more freely explore its striking environments and probe the boys' fantasies further.

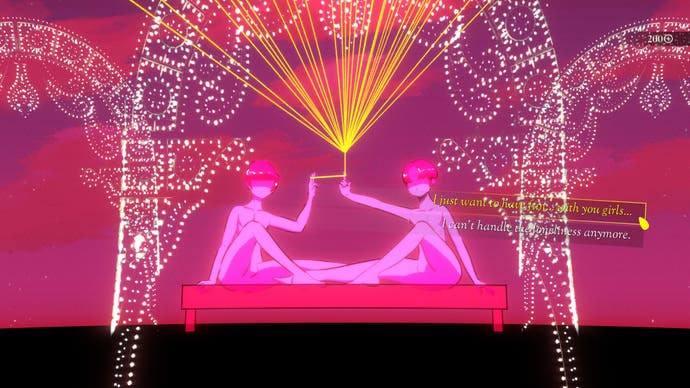

Andrea's first solo Mirage is one of hilariously unbridled horniness, a soft-core wet dream of beaches, beautiful men, and barely restrained innuendo as lollipops are licked, balloons are furiously pumped to the point of explosion, and fruit is consumed in startlingly suggestive ways (the boys' matter-of-fact queerness is refreshingly unabashed throughout Mediterranea Inferno, if usually a little more restrained). It's a sequence as gorgeous and frivolous and unbound as Andrea, a swirl of sun and skin and sweat, but there are glimmers of darkness too – here a disarming moment of unbridled terror in the face of loneliness – and it quickly becomes clear these visions of paradise are self-deceptions, a stubborn attempt by each boy to bury their deepest anxieties and lingering trauma, rather than confront them head-on. Claudio's Mirages are all baroque pomposity, conjuring intoxicating worlds and nostalgic lies of glories past, far from the present he refuses to face; Mida, for all his popularity, is wilful isolation epitomised – his first Mirage all cold, clinical abstraction and distance, playing out entirely at the bottom of an impossibly vast swimming pool, the real world just a square of light fathoms above.

It's easy to be dazzled by Mediterranea Inferno's stylistic bravado, especially during these Mirage sequences – from kaleidoscopic dance floor montages to noirish flashbacks, it's ceaselessly arresting stuff, as the 309 screenshots I took while playing can attest – but its real trick is how acutely it captures its moments of real, raw emotion. These boys might start life as a cartoonish portrayal of privilege – it's not an accident we're first introduced to them through the awed whispers of club goers, offering second-hand fictions with all the authenticity of an Instagram story – but their slowly unfurling pain and trauma feels profoundly, relatably real. These are rich, complex (if not exactly likeable) characters; disconnected from the world around them after several difficult years and caught in an unending cycle of deception – from themselves, their admirers, and their friends. Their inertia will ultimately be their undoing, and the increasingly ruthless Mediterranea Inferno spares no punishment for their self-pitying inaction (Madama mockingly refers to them as "martyrs" throughout), but their emotional turmoil is played earnestly, and handled with tenderness, empathy, and care.

Your role in all this is, admittedly, somewhat limited – conversations progress in linear fashion, and even though individual Mirages loosen control a little, they always reach the same conclusion – but the choices you do have feel genuinely impactful; once every morning and again each afternoon, in what increasingly feels like a simultaneous act of benevolence and extreme cruelty, players get to decide which of the boys can indulge in their perfect holiday escape and, thus, stand a chance of reaching their promised Heaven – it's no coincidence their trip culminates on Ferragosto and the feast of Assumption. But with only a limited number of Mirages possible each playthrough, and four Mirages being required for the final day's ascension, at least one boy isn't getting the endless summer of their dreams. "Starting tomorrow", Madama tells each unsuccessful candidate as their self-delusion comes crashing down, "you'll go back to your everyday life, everyday thoughts, everyday pain."

There's a malleability to Mediterranea Inferno that's not immediately obvious with a single, couple-of-hours playthrough; as Mirages are tallied on each boy's scoresheet, and their chances of an endless summer draw closer or slip further away, their demeanour changes, causing dialogue, cutaways, even entire scenes to shift – both subtly and dramatically – in a reflection of their current state of mind. An Andrea happy in his self-delusion is seen snoozing blissfully in one cycle of his summer, while an Andrea denied a temporary escape from his overbearing loneliness can also be seen at the same point in the story furiously, blindly swiping "yes" on his Grindr-style hook-up app, desperately seeking some – any – kind of connection.

Inevitably, as with any morality tale, a reckoning must be had, and when it finally comes time for one unlucky boy's delusion to collapse, Mediterranea Inferno's insidiously mounting horror takes a swerve into truly nightmarish excess – only for the "endless summer loop" to reset, so players can make different choices, explore different Mirages, reach different endings, and, if they've managed to track down eight elusive Santini cards during successive loops, taste one final "special" fruit for the ultimate truth within.

As deeply bleak as all this might sound, one of Mediterranea Inferno's most impressive feats is its deft handling of tone; while there are certainly moments of painful, sometimes disturbing, emotional frankness here – touching on depression, loneliness, trauma, and more – there are plentiful moments of light and levity too, albeit shot through a pitch-black lens. Madama's on-the-nose moralising is, for instance, delivered with the wryest of winks – an optional coda lays the story's allegorical nature bare, before hilariously undercutting its pomposity and hypocrisy to offer something like a hopeful ending for our boys – and it's probably going to be a while before I can shake Andrea's extravagant Catholic guilt porno from my mind. But beyond all this, there's the simple fact Mediterranea Inferno just spins a damned good yarn – a morality play built like a mystery, powered masterfully along through a propulsive peeling back of its layers.

There are big, ambitious themes at play in Mediterranea Inferno – the importance of community and compassion; the precariousness of safe spaces; an existential howl into the void for a generation stranded between a selfish past, a broken present, and a fading future; a call for action against emotional, cultural, and political inertia – and it can occasionally feel (appropriately enough) like it's losing its way amid its overwhelming concerns. Its emotional authenticity never wavers, though, and the result is a dense, provocative, playful, exasperating, horrifying, poetic, often very funny, and occasionally even profound rumination on the sometimes paralysing search for a place in the disenfranchising shadow of modern-day life.

Mediterranea Inferno might, like our boys, envelop itself in dazzling, distracting artifice, but like our boys, too, there's real, raw feeling in its bruised and bruising heart.