The dark romance of cars and nukes in Fallout 4

MAD motors.

From what I've played of it, Fallout 4 is a game about nuclear war inasmuch as the Narnia adventures are books about a wardrobe. Nukes may add a dark wit to a few of the central systems and give NPCs something to latch onto when they want to philosophise about humanity's endless cycles of violence, but their primary function seems to be ushering you from the character creation sequence and into the vast and brackeny post-America playground where the real fun takes place. Like Skyrim, Fallout 4 is a fantasy game. It's just that this time the fantasy revolves around the notion that there could be a meaningful kind of life following any decent exchange of ICBMs.

And I'm fine with this. Especially since, as Fallout 4 is an RPG, the kind of life it offers is actually incongruously pleasant. Sure, there are ghouls to deal with and bouts of radiation sickness to manage, but broadly speaking games built in this manner are about watching the numbers go up - and numbers that go up in games are generally fun. Each evening you return home stronger in stats than you were when you left it in the morning. You may have had to use some of your items, but you probably found a whole lot of new items in return. That radiation poisoning will clear up soon. You're ahead overall.

I enjoyed the few hours I played of Fallout 4 when it came out, I think, but - and I say this as a relative newcomer to the series - that opening 20 minutes before the bomb falls made me long for a little more of the real Cold War stuff. I spent most of those 20 minutes outside in my quiet neighborhood, taking pictures of the crazy retro-futuristic cars scattered around the place. I only remember this because I just found the snaps while deleting a bunch of old Steam screenshots. You'll know this feeling: digging back through all the games you've played and all the games you've forgotten playing, screenshots acting like layers of strata. And then suddenly I hit the Fallout 4 layer. Dozens of shots, and they're all of cars. Somewhere after I tired of photographing cars, I stopped playing - and I wonder if the cars might be part of the explanation for that.

These Fallout vehicles are confections, but only slightly. In the house where I grew up, my dad, an inveterate hoarder, kept a toy car he'd been given by a kindergarten friend on his fourth birthday back in 1947. It was a sort of Lincoln concept car: some green proto-plastic material with gold fins, a gold grill, and no visible wheels. The future of the past! Alluringly grotesque, here was a car fit for a world that was headed towards the apocalypse with the top down. Where they were going, they wouldn't need roads. They would be too busy crouched under their school desks. (My dad described the duck-and-cover drills he and his school friends were made to enact as "Lean forward, hug your knees, and kiss your ass goodbye.")

You could take that toy car, scale it up and stick it in Fallout 4. It would fit perfectly.The 1950s - which in Fallout's universe, continued for a whole century, by the looks of it - really were this crazy. The refrigerators looked like cars back then - or at least the grills and ventiports parts of cars. The cars looked like rockets. And the rockets? Everybody just loved rockets in the 1950s, regardless of the payload. In The Life and Times of The Thunderbolt Kid, Bill Bryson's memoir of suburban youth during Eisenhower's presidency, he mentions a plan that was hastily conceived to deliver mail by rocket. Letters arriving by rocket! It didn't seem to take off - no pun intended - but it probably wasn't for the lack of trying.

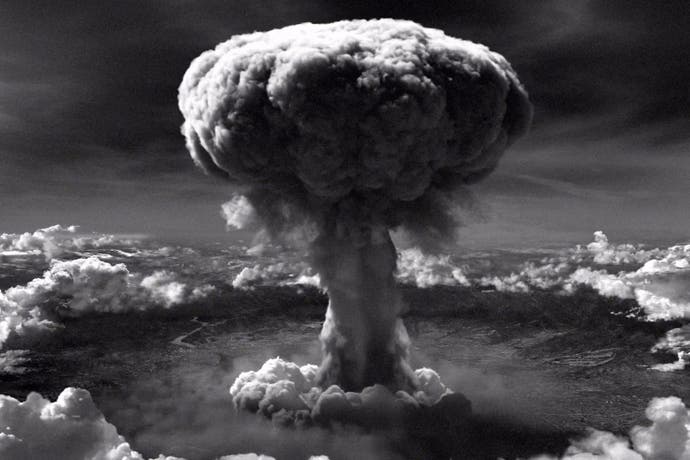

Where did all this misplaced energy end up? The kind of energy that decided cars needed fins and bubble tops, and that mail-by-missile had a future? "Nuclear weapons are everything and nothing," wrote Martin Amis back in the 1980s, when visiting Washington D.C., the nuclear city and the spot where so many ICBMs would converge in the event of a diplomatic disaster. In part, I think he was referring to nuclear weapons' dual life as ideas as well as objects - the fact that MAD (or Mutually Assured Destruction, the near-certainty that any aggressor in a nuclear war would be decimated in response) was a grim thought experiment that kept us safe through the human logic of game theory as much as the physical reality of the hardware that gave it heft. A while back, Martin Robinson and I went to an exhibition of atomic bomb-themed photography in London - small photos of very big explosions, arranged on the walls of an echoey room with polished concrete for flooring - and it truly was nukes captured in the abstract that made the most impact. We've all seen the mushroom clouds, and although the image is sufficiently vivid to avoid being rendered banal through repetition, they couldn't compete with some of the other photographs in the collection. A group of tourists, say, decked out in furs and sunglasses, sat in the desert in broad daylight. Except it wasn't daylight: it was nukelight, splitting the night open with a kind of man-made zombie dawn. Even better: a fake home filled with fake humans, piled on top of each other, waiting to bear close witness to the effects of a blast. Better still: an aerial shot of Manhattan, with a simple circle superimposed on it. Everything and nothing: nuclear terror invoked through a single spin of the drawing compass.

Fallout 4 toys with some of this stuff quite brilliantly, but a few hours in I remember that I could already feel its importance receding - at least for the time being. As I staggered around, trying to avoid the fights my stupid dog got me into and performing favours for the Minutemen, I found myself exploring a world in which nuclear weapons were actually no big deal at all most of the time. Radiation poisoning simply stuffed up the end of my health bar, and I could wave it away with an item or two from the inventory. Nuclear fallout made the wildlife into beasts, but I've been battling crazy monsters in every RPG out there for years, and these were really no different.

The only thing that really stuck with me was those cars, still covered in fins and cosmonaut bubble-domes, still ready for a bright consumerist future, but now rusting out in the Wasteland, piled up, wedged in ditches, relics of a sublime era of optimism and stupidity that brought about this collapse. The cars were a reminder: people did this, and we are no less ridiculous today.