The making of the Dark Urge in Baldur's Gate 3

How Larian honoured BioWare's story while creating its "most heroic" playthrough yet.

There are some pretty chunky spoilers here about the Dark Urge playthrough of Baldur's Gate 3, and perhaps one or two about other parts of the game. If you're still planning a Dark Urge playthrough of the game, I'd suggest going in as unaware as possible. Bookmark this for later.

Being evil in games excites me. I cannot resist the temptation of pressing a big red button. I do it because I want to see what a game dares let me do, and I do it because it's naughty. For months, I've been daring Baldur's Gate 3 to see how far it will let me go in my evil adventure, and so far, it's never backed down. I've pushed every red button I've found and the results have been extraordinary.

It's not common. Being a villain in a game is anathema to being a hero. How can you be one and also the other? This question has fascinated me for a long time, and it's why, when I first saw the Dark Urge option in Baldur's Gate 3, I was captivated. Here was a background option I could apply to my character that would implant some kind of unrestrainable evil in me - a murderous desire that could race forward and take control at the merest provocation. It could mean the death of companions and majorly upended story events. Was I ready to cede so much control to something in a role-playing game?

Yes. And as my Dark Urge story finishes, many months later, I can tell you it's been everything I hoped for and more. I've meddled with gods and become a literal, rampaging monster. The game has welcomed me. More than that, the game has rewarded me with a story stitched into the game's most foundational components. I am one of its major baddies, and to say it has slaked my desire for evildoing would be an understatement. I have revelled in it. The Dark Urge might have been revealed late in development, yet it's anything but an afterthought.

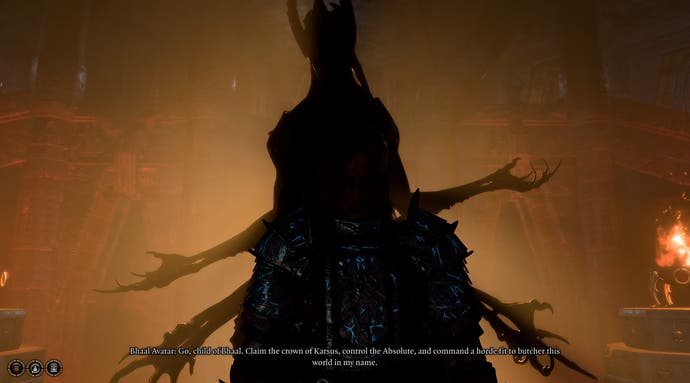

But the story of the Dark Urge began a long before Baldur's Gate 3, I discover. It began long ago with BioWare's original pair of Baldur's Gate games from the late 90s. There, the story of the Bhaalspawn was told. In the first game, you played as Gorion's Ward, a character beset by dreams of foul murder - sound familiar? They were dreams sent by the god of murder, Bhaal, who invaded your mind in an attempt to turn you to him. And he did it because you were his child, a Bhaalspawn.

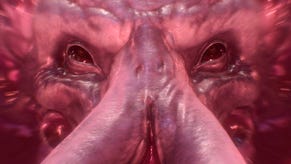

Baldur's Gate 2 continued the story but at higher levels with higher stakes. In this game you could become an avatar of Bhaal's, a monstrosity known as the Slayer, with spines and tusks and many clawed hands. Again: sound familiar? The story of the Bhaalspawn tied those old games together. That it should reappear in Baldur's Gate 3 was something widely expected by fans, which is precisely why it had to be hidden when it entered early access in autumn 2020. It was a fake-out.

"We didn't want to give away that it was going to be there," writing director Adam Smith tells me, speaking on a video call from Larian's HQ in Ghent, Belgium. "It was like the ace up our sleeves that we will have this thing." That the Bhaalspawn would feature in the game was never in doubt - the words "Bhaalspawn companion" were on the original pitch documents, Smith recalls. "It was always going to happen." The problem was: how?

To be clear: at this point the Dark Urge didn't exist - that is a manifestation that's entirely unique to Baldur's Gate 3. A lot of the initial thinking was done by principal writer Jan van Dosselaer, who provided a backbone to the story you can still feel in the game. But a lot of those early ideas were falling on infertile ground. "We went through god I don't know how many versions of it," Smith says.

It was complicated. On the one hand, there was patchy historical continuity with BioWare's earlier games to consider: it wasn't clear what happened to the Bhaalspawn after the events of those games. Did they wipe each other out? Where were they now if they didn't? And how would a new character in Baldur's Gate 3 be related to them? Larian also wasn't sure what role the Bhaalspawn character would play. Would it be the player character or a companion? The studio tried the latter, having a Bhaalspawn companion who, as Smith says, "keeps fucking up and doing things". But because you weren't in their head, seeing their struggle, it wasn't very captivating. "It's probably more interesting if I play as it," Smith and the team thought.

Smith took an early swing at the Bhaalspawn idea that could have drastically changed the game. "This never got beyond paper," he says, "but the idea with this was: you wake up one day and the dream companion you made at the beginning, you have a dream with them in it and their head's been cut off and there's guts splattered everywhere and someone else has replaced them. They come up to you and say, 'I'm in control now.' And it's Bhaal. He just steps in and he says, 'Fuck them - that's finished. You listen to me.'

"We had this thing where he literally forced the tadpole out of you," he says. "He was like, 'No, no, no. I'm the one who's in charge around here.' Well, he pushed it to one side and it had no influence on you any more. So then it became this inner struggle between Bhaal and a tadpole and your own personality. It was too much. It's the kind of thing that might work as a TV show; it didn't work in our RPG."

Nothing the studio tried worked well across the entire game. It needed something else. It needed Baudelaire Welch.

Welch was hired by Larian just after the early access release, so in the autumn of 2020, and they were initially brought in to oversee companion relationships in the game and expand on those storylines. Taking the reins of the Dark Urge wasn't even a consideration at that point, but that didn't stop them from trying to solve the problem. "Beau had this idea which was like, 'What if it's watered down so much that you're something different?'" Smith says. "Almost like you've become this deranged leftover." And suddenly, everything clicked. It gave the character distance from Bhaal and the murderous desires were - like the mind flayer tadpole in your head - an instantly understandable idea. They barely needed to be explained.

"Beau managed to crystallise it in a way where it feels human," Smith adds. Intrusive thoughts: people get it. "And you need that because you're already asking people to take in a million different names and words and proper nouns. I don't want the player to have to think, 'Oh, I'm five generations removed from Bhaal' - that's really boring. What I want them to think is: 'There's a fucking voice in my head making me do things I don't want to do'."

Welch didn't expect to be offered the task of writing the Dark Urge, but Larian founder Swen Vincke, creative director of Baldur's Gate 3, had heard an interesting piece of trivia about Welch's family. "My mother worked partially on the script for Silence of the Lambs, the movie," Baudelaire Welch tells me now, in a quiet room at the Develop Conference in Brighton. "And I think Swen got that in his mind a little bit like, 'You'll be good at this'." So one one day, Vincke called Welch into his office and made a seemingly innocuous offer: "Why don't you try writing some of the first Dark Urge dialogue?"

There was a problem: Welch wasn't like their mother in one crucial regard. "I'm so squeamish," Welch blurts, laughing. "I hate gore!" How on earth would they write the depraved thoughts of a murderer? Yet it was precisely this squeamish nature that Smith believes made them the ideal candidate for the job. "The reason Beau was so good at that is when you get somebody who is really into gore and horror, they want to make it cool," he says. "Beau had this sense of, 'I need to make it slightly ridiculous, and I need to make it slightly grotesque in a way where you're like, 'eurgh!'

"That came from somebody who's like, 'This stuff is fucking horrible!' That gave it something I couldn't have brought to it; that somebody who's written 30 years of horror couldn't have brought to it. It was that squeamishness that actually made the delight in it kind of perverted and weird, and idiosyncratic and strange. What we didn't want," he adds, "was 'I'm the Dark Urge, heavy metal, [guitar solo sound]. Fucking rivers of blood man - cool!'"

Welch's way of dealing with it was deliberately not to write gory scenes. "I didn't really want to write all of these lascivious descriptions of things that were really disgusting," they tell me. Instead, they had the Dark Urge imagine things in a more abstract way. Consider the scene in the Druid Grove where you're dealing with an injured bird, for instance. "The average player sees it and helps heal it," Welch says. "If you're the Dark Urge character, you get the option to think about tearing its wings off. And when the Dark Urge does it, it doesn't describe doing it, it just says - while the Dark Urge is tearing off the wings of this bird - 'You wonder what it would be like to fly as the birds do.' It's more disturbing because it's a psychological reaction to it rather than, 'Oh, here's the thing you're seeing in front of you'."

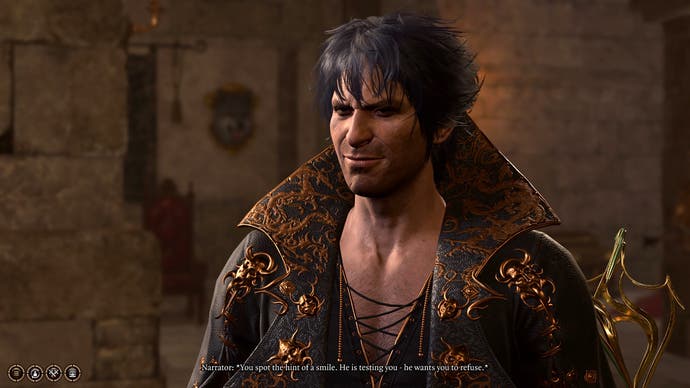

Welch also came up with another crucially important vessel for telling the Dark Urge's story: the butler. Part way through the first act, you're visited in the night by a goblin-like character hailing you as their master. He wears a top-hat and tails and radiates malice, though in a ridiculous, pantomime kind of way. And he's full of encouragement for your dastardly deeds. The role he plays is twofold: along with the thoughts in your head, he provides the encouragement you need to actually do the evil things in the first place, as Welch believes "players aren't going to ever play an evil character unless they're actually having fun with it - unless they feel a real reason to be encouraged to do it".

Secondly, the butler tries to desensitise you to what you're doing, making it all seem harmless and silly. It's an idea inspired by Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange novel. "I was really inspired by Clockwork Orange specifically because there's an unreliable narrator in [it] who encourages the reader to just think that what's happening is a bit of 'naughty fun'," Welch says. "And that's what the butler character is inspired by, that this is just meant to be a bit of naughty fun going on."

Sceleritas Fel, as the butler is known, didn't exist in the earlier Baldur's Gate games. There was a Butler of Bhaal, an imp called Cespenar, but they only played a minor role forging weapons for you. Still, it was enough to provoke the idea that the Dark Urge might have a personal servant of their own, and one who might slowly fill in your memory and act as a go-between for you and Bhaal. It was a character Welch had a great deal of fun writing.

One of their favourite lines coincidentally belongs to one of my favourite Dark Urge moments in the game: the moment you get the monstrous Slayer form. Sceleritas Fel promises you a reward if you kill an important character called Isobel, and if you do, he shows up with a gift for you. "I have something wonderful for you, dear mouldering Master," he announces, snivelling with malice. "A part of your past is here for you. Try on your new jimjams! They're a present from Father, it would be rude not to."

Jimjams? I remember in that moment wondering what Fel meant. Did he really mean pyjamas? Not that I'd refuse them - I could have done with some nice new clothes to wander around camp in. But before I could think any further, my character arched back in agonising pain as a transformation gripped them, and in a shower of gore they became something more - a 10ft killing machine.

"I was amazed it didn't get cut," Welch says, referring to the jimjams line. "That's what I'm talking about: wanting it to feel like it's being playful and joking around with Baldur's Gate 1 and 2. You'd think receiving the Slayer form was the most badass thing imaginable [...] something that many games would treat like it's an untouchable part of the IP - 'We must treat it with due reverence' - so being playful with it was part of the fun. I'm glad that you remember that line!"

Nevertheless, for all the abstract descriptions of violence and for all the good humour, writing the Dark Urge took its toll. "I said I was squeamish at the start," Welch says. "It desensitised me to everything."

It can't all be humour though. For the Dark Urge to work - for evil to work - it has to have consequences.

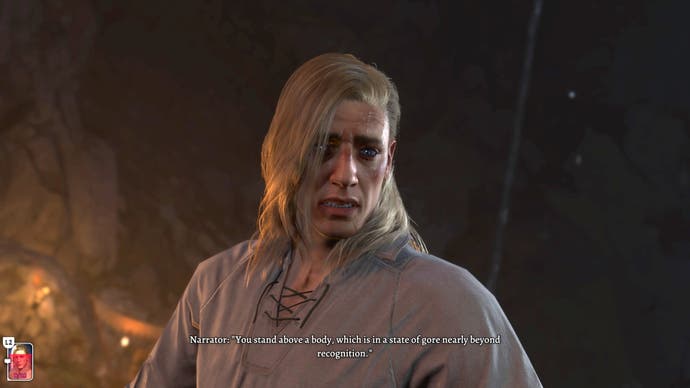

One such moment happens early in the game when a tiefling bard called Alfira joins your camp. They ask if they can stay the night; it's a big mistake. If you're the Dark Urge, you will dream about savagely attacking her to wake and discover it has come true. And it's a disturbing scene: her innards have spilled from her stomach and her face is twisted in an expression of agony. It's a sharp reminder of what you can do.

It's actually a moment that breaks Larian's internal design rules, Smith says, in that it happens and you can do nothing about it. "It was really important to us that you actually do awful things and that it wasn't a case of, 'Well I can just avoid all of them.' We knew at some point you were going to discover that you've done awful things in the past, and that's all well and good, but we were like, 'No, you need to actually experience it.' It's show, don't tell. You need to experience having done this at least once."

In other words, the Dark Urge needed moments for you to reflect. Being evil shouldn't be easy. I've felt this myself as I've tried to do every bad thing the game has offered me; more than once I've struggled to stay the course. When I betrayed the Druid Grove in Act 1, for instance, I lost sleep over what I was about to do. And when Minthara's goblin army swept in and killed everyone inside, even children, I felt wretched about it. As I should. I felt similarly despicable when I destroyed the refuge of Last Light in Act 2. "We did try and make it hard, emotionally," Smith says.

There were also moments where I felt the game was interrogating my motivations. I distinctly remember the tiefling leader Zevlor turning to me after I let the goblin army into the Druid Grove, asking - no, imploring - why I had done what I had. I was taken aback. "You're right in that there are points where the game is saying to you 'are you fucking serious?' through characters," Smith says. The drow commander Minthara, the baddie in Act 1 but who can become a companion, exemplifies this. After the Druid Grove, when you expect her praise, she turns and says: "I was under mind control when I killed those tieflings - what was your excuse?"

"We didn't want you to just be able to walk away from that and say, 'Oh,'" Smith shrugs, "'You know.'"

It's a lonelier road, too, the evil one. I didn't have the companions Gale or Will or Karlach or Halsin or Jaheira in my adventuring party, because they all either left me or are dead, which means I'm missing a considerable amount of written story content. "The idea was that the evil route was the lonelier route," Smith tells me, though he accepts feedback from the community that it was perhaps too content light. "We probably should have given a little more," he says.

But how people play the game is a variable Larian would never want to control, because that's what a Larian game experience is: your experience. Having an intricate clockwork system of choice and consequence is at the heart of everything the studio does and will continue to do. There are always going to be ways people approach the game Larian couldn't predict.

What surprised Welch was how many people played the Dark Urge and tried to resist it, and Bhaal. "I wrote the Dark Urge character with the 'giving into Bhaal' plotline always in mind," they say. "I was always writing with 'evil evil evil evil' in my brain." They tell me it hadn't really occurred to them how many people might want a happier ending from it, but one scene in particular that they had to write helped to change that. Near the end of the game, at the culmination of the Dark Urge storyline, the player can resist Bhaal for good. "I was told to write this as a really nice thing and I wrote a single draft of it, and I was like, 'This is the corniest thing I've ever written,'" Welch says.

But Smith, like many players, loved it. To him it was a rare moment in Baldur's Gate 3 where a god does get involved and intervenes for the sake of the people of the world. Usually the gods treat you like toys, which is a running theme in the game. "[Baldur's Gate 3] doesn't show a very rosy view of deities," Smith says. But here, Withers, a character who's been in your wider adventuring party since the beginning - and who you find out is a god in his own right - steps in, and effectively says, as Smith puts it: "Fuck them. I don't think this is fair. You're a hero. You don't deserve this shit."

It's a lesson about the value of happy endings that Welch has learnt from working on Baldur's Gate 3. "I learnt over the course of working at Larian, the value of how much a happy ending could end up pleasing people or end up making people feel a sense of accomplishment," they say. "People get a lot of reward out of being a good person. I've seen the degree of meaning of overcoming something as big as the taint of Bhaal that players have got out of this."

There was a misconception when the game launched that the Dark Urge was solely there to encourage and perpetuate evil playthroughs. I'll admit, I thought of it in the same way. But within the Dark Urge lies great potential for heroism - exactly the same kind of heroism you experience in the earlier Baldur's Gate games. "I've said this a lot of times," says Smith: "it's the most heroic playthrough. Because it's the one where you were born with something that is not your fault, that was put into you, and you overcame it."

Just as important to the feeling of being evil in the game is the studio's commitment to, as Smith calls it, contrasting choice. This means making sure there are significantly different choices people can make, rather than just slight variations - sarcastic, gruff, enthusiastic - of the same choice. "As soon as you do that and you have that as a design principle, you can't help but say, 'Oh god what if they want to do that?' Somebody's probably going to want to because it's roleplay.' That leads you to having to cater for very, very broad choices." You don't, after all, have to be the Dark Urge to be evil in Baldur's Gate 3. One of the most reprehensible things you can do is pressure Astarion into being intimate with you, which doesn't have anything to do with being the Dark Urge. Similarly, Will can behead Karlach for motivations entirely his own. Evil does not depend on being Bhaalspawn.

"You'd be surprised by how many people you present evil options to and not only do they not want to pick them because they don't feel they fit the roleplay, but they don't pick them because they think, 'They won't really let me do that," Smith says. Baldur's Gate 3, though, does, as I well know. Realising that takes a lot of work. It means being prepared to cede control of the story to the player and their not seeing a lot of your work. Consider Minthara: she's a companion for me but most people will have fought and killed her early on. All those great lines and romantic moments won't exist for those players, in the same way I haven't experienced a handful of companions' stories in the game. "It's us sacrificing a huge amount of work to say, 'Your choices matter,'" Smith says - and it's an entrenched design philosophy at Larian that's very much there to stay.

There are some things Welch would have liked to have done differently with the Dark Urge experience. Simply, they would have liked to have more Dark Urge moments throughout the game. There are clusters of Dark Urge activity around the main story beats in an act, but away from them, they drop off. There were practical reasons for this: a lot of work on the game had already been done by the time the Welch took the Dark Urge into development, so things were laid down and there was a limit to what could be done. It would also have been nice to see more of the Dark Urge cinematically, Welch says, though to Larian's credit, it is working on this now, post-release. The in-development Patch 7 will bring much-needed, expanded evil endings to the game. As it is, it ends rather abruptly, but these should extend it greatly. Smith is really excited about what the team has done. "The cinematics team and Bobby [Slavov, composer and musical director] on the music: fuck me, we knocked it out of the park," he says. "It really pays off the fantasy of 'I just did everything bad in this game and here's the result'."

The only other thing Welch personally would have done differently is recognise the unexpected Gotash and Dark Urge romance potential in the game. Welch has a long history with fanfiction, and has seen people shipping the two characters. They're slightly ashamed they didn't see it sooner. "I believe in the Dark Urge x Gortash ship wholeheartedly," they say, "but I never saw it coming. I think we always imagined that Gortash was going to be an 80 year-old man over the course of development, and then we saw his model and it was like, 'Oh!'" Then actor Jason Isaacs was cast and provided a purringly sinister performance, and all of a sudden, Gortash was a 40-year-old emo hunk. "I so, so, so wish that I had seen that coming and added some optional hints of reactivity into that whole thing," Welch says.

The only thing Smith says he would have done differently is make the Slayer form more powerful-feeling to use, which, from personal experience, I think Larian now has. I certainly ripped Orin apart easily enough in our duel. Outside of that, Smith is pleased with everything the studio has achieved. "Which doesn't mean that I think we did it perfectly," he adds. "It's just that I'm very proud of it, and I think if we changed one thing for the better, we might have made another five things worse. That's how delicate it is."

For me, the Dark Urge and Baldur's Gate 3 have set a new standard for what evil playthroughs in games can be. From the outset, Larian embraced something few other games do, and through it, delivered something wickedly funny, profound, and more fulfilling than any evil playthrough I've ever experienced. Despite preconceptions, the Dark Urge is no mere second playthrough afterthought. It is the game's best kept secret, the glue that binds a series together, and the temptation to behave in a way you might not have before. It's the perfect encapsulation of how deeply Larian values choice and consequence. It is, perhaps, the best of Baldur's Gate 3. You just have to have the nerve to play it.